I began leaning into poetry thanks to the matriarch of Christian poetry, Luci Shaw, when I read her first book “Listen to the Green” in 1973. Luci is a poet who, more times than I can count, has sent me scurrying to my Webster’s dictionary. I recently read the word ‘haecceity’ (heck see it ee) in Shaw’s poem “The Haecceity of Travel” (Books and Culture, 2015, online) and was clueless about both the pronunciation and meaning. But good poems do that—and because I’ve always been a word nerd I’m happy to stop reading and look up a word’s definition.

Haecceity literally means “thisness,” the state of something being itself and nothing else, coined by Duns Scotus in 1600 something. I doubt I’ll ever use the word in a sentence but I like knowing its definition. Plus it’s fun to say.

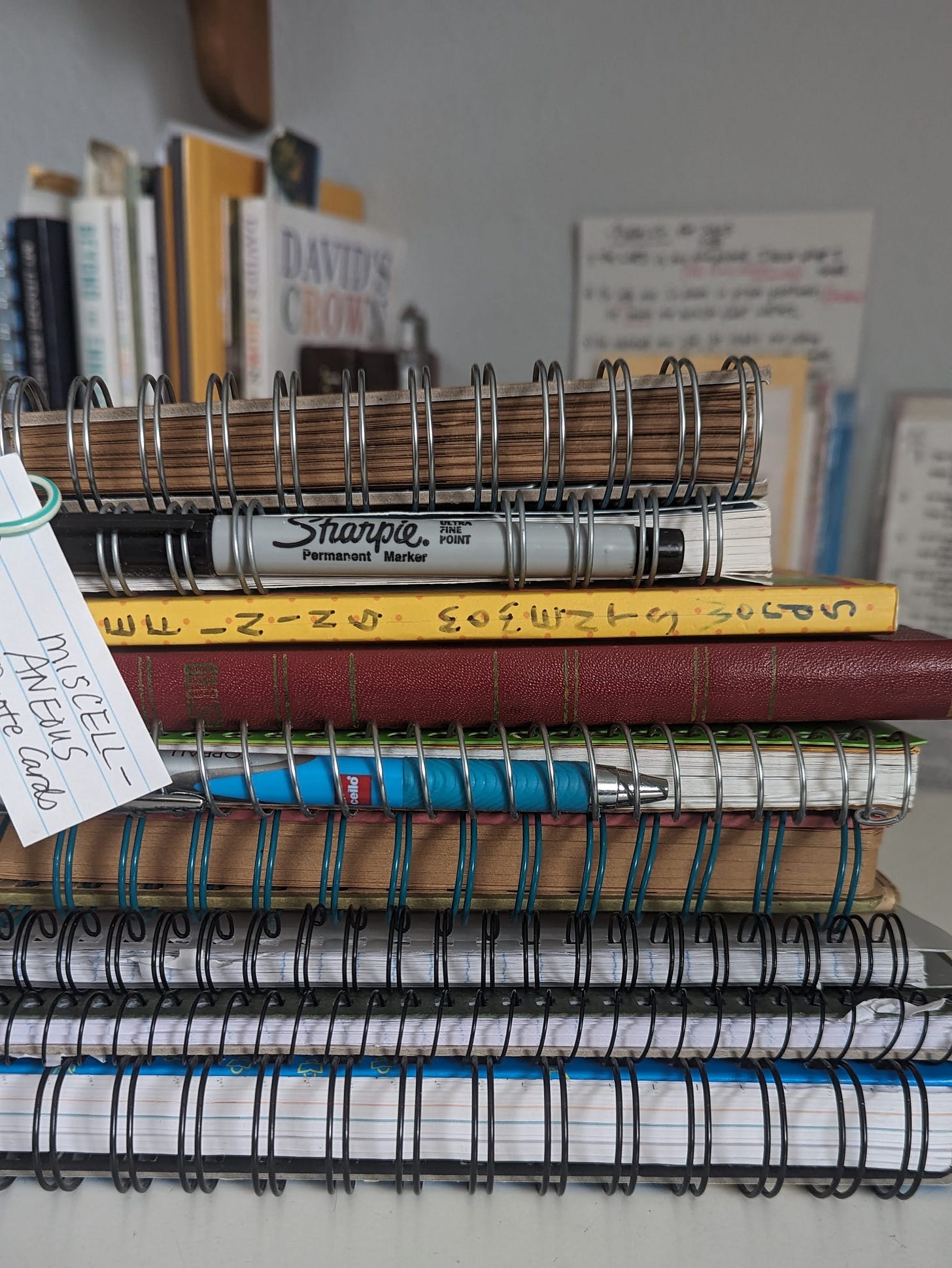

There are so many other words that roll across the tongue or around one’s mouth, providing the coinage to spend on a poem. I keep my discoveries in a ‘New Words’ journal, a slim Moleskine with entries of words I’m not familiar with, the source (book or poem) and the date I read it. There are descriptors like mellifluous or evanescence, nouns like martello (Anne of the Island, L.M. Montgomery), or panegyric (from Jane Austen’s Pride & Prejudice) . Not only are these words a great pronunciation workout, they can often provide the kernel of a poem.

In addition to my “New Words” journal filled with sticky notes adhered in place until I look up the definitions of quickly-scribbled words, I have another volume titled “Defining Words.” This slim notebook contains pages with a single word on each and a list or web of the word plus its many uses. Linguistically I enjoy the hunt for root words and untangling a word’s usage and meaning; often yielding a think tank of poem ideas. Hanging out in my son’s Latin enrichment class in grade school twice a week really paid off.

There are words like

Sound—body of water

Sound—that which you hear

Sound—is _______ strong?

Or

Score — in music

Score— in a sporting event

Score—with a knife

Another bottomless word

Veil—long white diaphonous covering

Veil—to reveal something is to un veil it

Veil—to hide or cover

The possibilities are endless. Bound, fare, temper….

So. Language matters. And good poetry, in my humble, entirely subjective opinion, is driven by the choice of language: vivid verbs and descriptors, metaphors that contain meaning as well as emotion. (Granted there are a number of other qualities to make a poem ‘good’, I am merely scratching the surface).

The bedrock of poetry is its form-written in verse, from the Latin word ‘versa’ meaning to turn. Contrary to popular opinion, poetry is not the opposite of prose; they aren’t two different genres, they are two different forms.1 The text in prose is formed by sentences which run to the edge of the page and wrap around. There are a multitude of genres within prose—humor, romance, historical fiction, memoir, sci-fi, fantasy and so on.

So when writing a poem, how do we get readers to ‘turn’ (the meaning of verses, from the Latin ‘versa’) and keep on reading? How can we engage them to continue to the ‘aha’ of our last lines? To write a good poem (see above), in free verse, the form I frequent the most, attention must be paid to the words not only in the middle but at the end of each line, encouraging readers to move along and turn to discover more.

My poetry writing practice has entailed paying attention to revising and rewriting my initial drafts until they rise a bit above the easy dullness with which they begin. I look at shortcuts. Where have I used a cliche or a tired word? How can I replace them with something more telling or picturesque?

And what about all my ‘that’s? Always too many of those. And the sentences that end with a preposition. Remove them, even out your line lengths, add a poly-syllabic descriptor, grab a thesaurus or dictionary, again. (I probably mixed pronouns there. Sorry).

Also, how does my poem look visually? Will a reader sense a flow in the words or is it chopped up? Pay attention to using too many articles. Do I truly need all those ‘the’s’? How are the verbs? Is there movement or do they fall flat? Too many ing endings? (A tendency of mine.)

The only way to discover this of course is to read your poem out loud. (Always my first rule when I taught Writer’s Workshop to Middle Schoolers.) How will you know what your work sounds like or its meaning until you hear yourself say it? My favorite poet Malcolm Guite once said, “A poem comes alive when it is read.”

I agree. Prompted by the sound of the word ‘mellifluous’ I imagined the possibilities the picture brought to mind and wrote this:

Liquid Light

Oh Rock in which I hide,

Would that sticky gold

Could drip from my lips,

Add invisible sweetness to those

In need of shelter in this storm

Of words.

Pour from this server, cascade, stir

Slow and careful, leaving mellifluous

Life in today’s cup as it passes by.

Drip and pour.

Stir and stay.

Honey.

Question for you….What do you notice about the shape of this poem?

And tell me, if you write poetry, where do you gather your words to find inspiration?

Scott Cairns, poet, Professor and Director of the MFA in Creative Writing at Seattle Pacific University, enlightened me on this via an essay in “A Syllable of Water”, Paraclete Press, 2009.

Ishah, I'm so glad you happened upon my space here on Substack!

My aim is to help people make friends with poetry, especially the writing of it. It's so funny you mentioned a commonplace book, I'm working on something called Gathered Words to add here on my website soon. It's a compilation of a virtual bulletin board sort of space to collect all the many many quotes I've got written down in journals and notebooks over the years.

Inspiration is everywhere!

Agreed! I learned that from Scott Cairns via his essay on poetry in A Syllable of Water, published by Paraclete in 2008. The essay is called "A Troubled and Troubling Mirror." It's so great to learn new things in this writing life, isn't it?