3 Reasons to Read Poetry if You're Writing It

And a list of 25 Christian poets to begin your reading

It is a truth universally acknowledged that a good writer will also be a wide reader. My own work has been greatly informed and influenced by reading the words of many other Christian poets over the last several years, both contemporary and classical. This active pursuit of poetic learning began in earnest in 2016 when I started attending workshops, panels, conferences and readings, hounding introducing myself to poets whose work I admired, often handing them a copy of their most recent book to sign.

Each and every one has been more than gracious to accomodate my interest (fangirling) and enthusiasm, offering kernels of wisdom and teaching me so very much. For don’t we all enjoy sharing what we love with others?

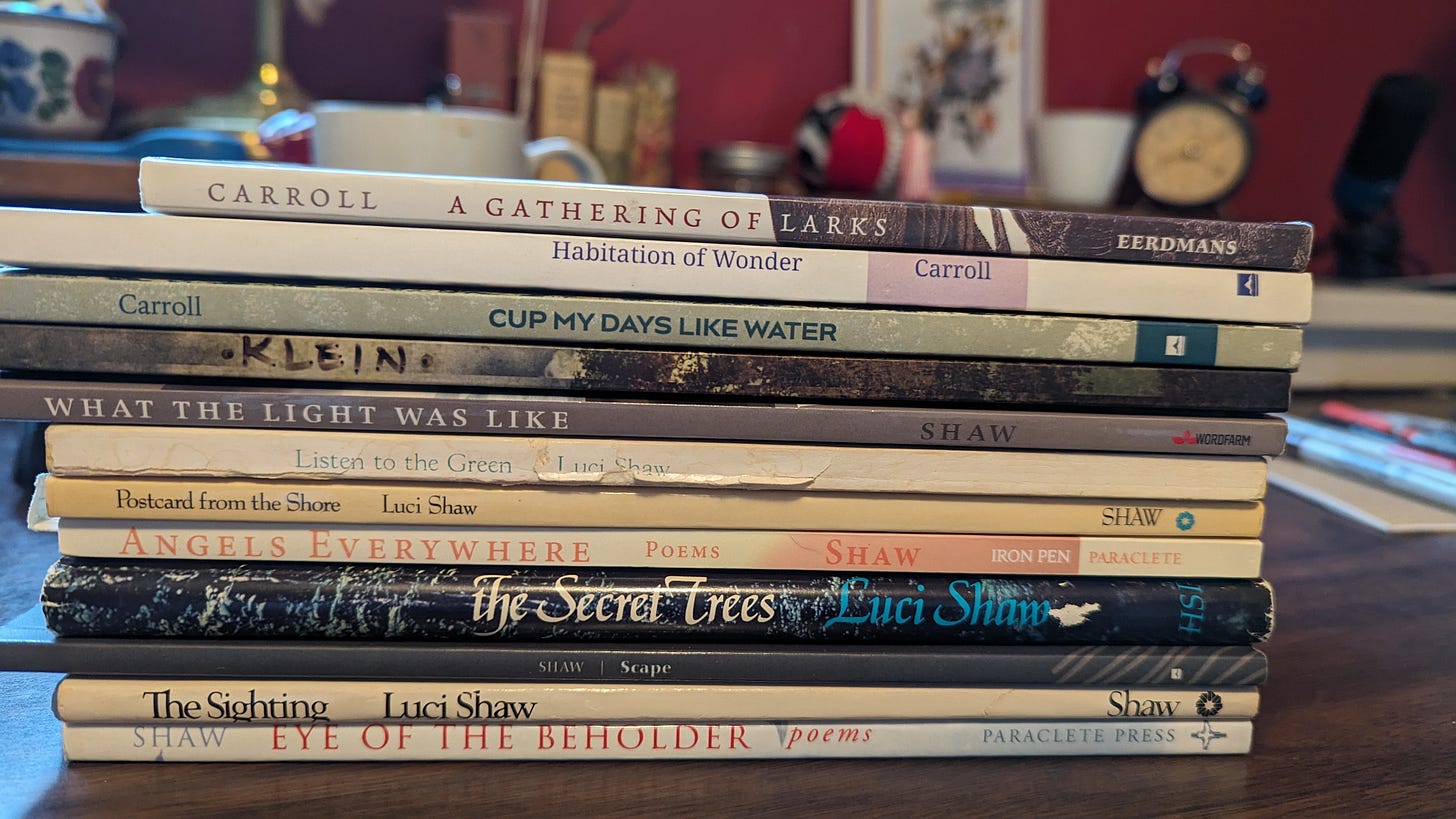

When I first began scribbling my poems, most of what landed on the page was very bad “poetry,” and pretty cringe, but it was a beginning. As I chose to grow and learn, I invested in an informal education--"The School of 3,000 Books,” as poet Barbara Crooker has said. My poetry today is inspired by contemporary Christian poets like Abigail Carroll, Laurie Klein, Scott Cairns, Christian Wiman, Malcolm Guite, Luci Shaw, Laura Reece Hogan and others, along with classical writers like George Herbert and John Donne.

I have an elementary Teaching Credential and a B.A. in Liberal Studies; I was not a writing or English major in college, thus everything I know about writing a good poem I’ve stolen from many other fine people. And of course I mean ‘stolen’ in the best way. Many, many of the poets in the list included here (scroll down to the bottom of the post) have influenced the poems in both of my books-Mining the Bright Birds: Poems of Longing for Home and Hearts on Pilgrimage: Poems & Prayers.

So here you are, three reasons to read other peoples’ poetry if you’re going to be writing it.

1. Reading other peoples’ poetry offers seeds for new poems of your own.

I heard Malcolm Guite say in a workshop once, “A good poem is both generative and generous.” In other words, not only will the poem offer something in your reading of what’s actually on the page—an image or emotion that resonates deeply, the generous part—but it can also offer a springboard to respond with a poem of your own—the generative part.

When I first read poet/priest Malcolm Guite’s work, I was drawn in not only by the gospel-centered content but also the remarkable sound and cadence of the language. I've tried my hand at writing my own sonnet, Guite’s specialty, and they are hard to write! Malcolm’s encyclopedic brain can bring up hundreds of poems he’s memorized because of their rhyme and rhythm, a motivation to me and evidence as well of the power of rhyme and meter when it comes to recitation.

Of the seven or so Guite books I own, my current favorite is “David’s Crown—Sounding the Psalms,” where he wrote through Coverdale’s Psalms (from the Book of Common Prayer) responding with a sonnet for each one. These were written during the pandemic and Guite wove the last line of each of his sonnets into the first line of the next. A ‘corona’ or crown, if you will, completing a circle or cycle of poems (after John Donne’s form in La Corona, a cycle of seven poems.)

In David’s Crown Guite begins his response to Psalm 30, ‘Exaltabo te, Domine’,

He gives us too, a voice to sing his praises,

This line became a seed for my own short response, which then became the opening poem in my book, Mining the Bright Birds.

He gives us means to write his praises

The breath to carry every thought

To hearts and out again to raise us

Above, mere creatures whom He has wrought.

We alone hold pen and ink,

Brush and pencil paper thin,

No other image bears his likeness

But ours His work to enter in.

A writer here on Substack, Steven Searcy, has a wonderful book of rhyming poetry Below the Brightness (released by Solum Press) which has also been an inspiration to me. The poems are less formal and sonnet-like but filled with beautiful and appealing cadence and meter. (And feature an endorsement from Malcolm Guite.) Here is Searcy’s poem ‘Hush’

Much noise surrounds.

Let words be few.

Sit.Listen.Chew

Then hear the sounds

of trees and birds.

Sit. Breathe. Release.

And taste the peace

too deep for words.

I responded with my own small poem—

A Rhyme of Wonder

Too immense for words and yet we try

Earthly earth,

Cerulean sky

To share the wonders that must be heard.

Take up your pen

Write it down

Let language resound

And resound again.

We must needs tell

Lest the rocks cry out

And offer their shouts

To break the spell.

2. The second reason to be reading poetry if you’re writing it is to learn form, sound, language and vocabulary.

I always have a pencil in my hand when I’m reading, underlining and making notes in the margin as I go, with poetry especially. There are scads of notebooks on my shelf, journals filled with new words I’ve learned (and mean to look up later). New vocabulary alone is one reason to be reading other poets. I’ve discovered some poly-syllabic wonders, words like: marcescent and alterity and mellifluous. The mouth feel and sound alone is a joy and any poet whose work sends me to my dictionary is an immediate friend and inspiration.

Another reason to read with a pencil in my hand is to underline and make note of the forms, particularly sonnets and the meter and cadence of rhyming poems, but also to make note of the way a poet uses line breaks in free verse.

I notice several things:

How does the poem look visually? Are the line endings even-ish and therefore pleasing to my eyes? (This is a personal preference but a strong one.)

Where does the writer place the ‘turn’ in the lines, (which is the meaning of verse, from ‘versa’ meaning to turn) that moves me along to the next line?

And how can I model the poet’s form itself—primarily when it comes to sonnet-writing—to write a poem of my own?1

3. The third reason to read other poets is to find what resonates with you—the images or emotions—and write that way.

When I say ‘write that way’ I don’t mean to mimic them, but model your work after theirs, to say the same things you feel or see in your own, descriptive way.

What images or emotions come to the surface while you’re reading?

What thoughts or feelings resonate, causing you to say, “I totally can see that,” or “that’s exactly how I feel”?

The way a poet offers new metaphors can be an inspiration that informs your own poetry, giving examples of a physical object as a bridge to an abstract idea or feeling (which is the definition of a metaphor). Poets whose work does this strong images with which to identify have taught me how to look at everyday objects as ‘containers’ if you will for images and ideas.

How is my life like a shell? What does a leaf carry in its way down to the grass? How does a bowl hold something? All of those objects can provide new ways of seeing and thinking.

25 Christian Poets—Where to Begin your Reading (free download button below)

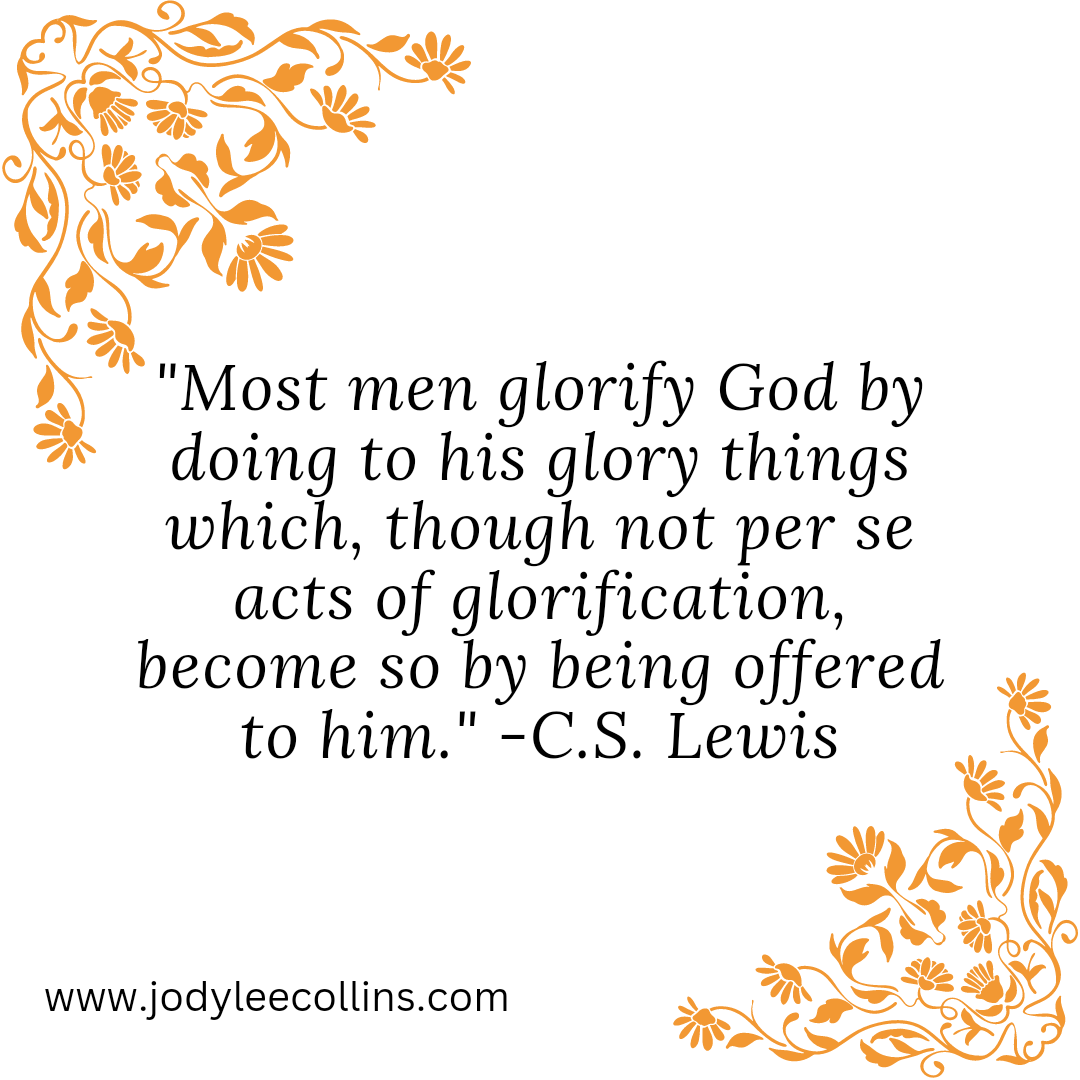

When I mention Christian poets I do not mean necessarily writers of only biblically-centered, gospel-oriented content. No. I mean writers whose work brings glory to God through its ingenuity, creativity and in the way it points people in the direction of our Creator, as C.S. Lewis so brilliantly says. Even if, and often without, mentioning the name of God.

How?

25 Christian Faith Poets-Classical to Contemporary

1. Abigail Carroll

2. Anne Bradstreet

3. Anne Porter

4. Anne Ridler

5. Barbara Crooker

6. C.S. Lewis

7. Christian Wiman

8. Christina Rossetti

9. George Herbert

10. Gerard Manley Hopkins

11. Jane Clement Tyson

12. John Donne

13. Laura Reece Hogan

14. Laurie Klein

15. Luci Shaw

16. Madeleine L’Engle

17. Malcolm Guite

18. Phyllis Wheatley

19. Richard Wilbur

20. Sara Teasdale

21. Scott Cairns

22. Seamus Heaney

23. Susan Cowger

24. Tania Runyan

25. Wendell Berry

Thanks for reading Poetry & Made Things! Consider subscribing for more inspiration and free resources.

Copying poems is a remarkable way to learn; starting a Poetry Notebook is a simple way to do this. Print out the poem you like, 3 hole punch it, add it to a binder with a sheet of blank paper to pen your own thoughts/response… or maybe write your own poem! Over a year, you will have a rich collection.

HERE is a great resource above to do just that, something I created for copying and learning poems to inspire you; I call it PoetScribe.

Thanks so much for this great article. A lot of it resonates with me and reminds me of my own poetic journey. This one’s a keeper!

I just came across this post. Thanks for mentioning my book, Jody. I'm so grateful to hear that it's helped inspire new writing for you! Reading more classic and contemporary poetry is definitely a crucial practice for any writer, at any stage - it's great that you're sharing lists of good starting points to help others along the way.